Firefighters

.

“I will never allow personal feelings, nor danger to self, deter me from my responsibilities as a firefighter”

-Firefighter Code of Ethics

.

When your life takes a sudden turn and the unexpected lies before you, the simplest of questions appear overwhelming and relying on others for assistance becomes a temporary way of living. It’s foreign ground. Only trust in the guidance sustains you.

.

To understand a firefighter completely and not be one yourself means you’re married to one or pretty darn close to one. Michael considers it an honor to be a firefighter, and I can do nothing but to honor him in discovering and living his passion. Firefighters are a complicated breed. Their common features extend beyond state lines and even national borders. But the thing is--the very thing that drives you nuts about them--is also that thing that makes you love them. Michael is great at what he does; yet he, himself, would never admit to anything more than being just one of the guys within this group.

.

I started anticipating the events of September 11, 2001, about six months before it happened; about four years before cancer would hit our family. Everything came in the form of dreams up until August. Then a terrible sadness started hitting me in the middle of the day, with no apparent trigger. I would be driving and find myself needing to pull over because I couldn’t see through my tears. The wave of emotion would last a few minutes, and then I could carry on with the rest of my day.

.

Benjamin was three and Abigail, one, when the towers fell. I had slept in that morning, something I never did. I woke up when Michael came home, still in uniform from all-night duty. “There has been a terrible accident.” He was almost stuttering. “They think a small plane has hit one of the twin towers in New York.” He was gesturing, his hands needing a task. He actually started signing “accident” and “plane.”

.

Later, the facts became clearer, the horror documented in every media format on earth. I found myself clinging to specific stories. “I want to know how the buildings were built! Why did the chiefs send those firefighters up into those buildings? Planes have hit those buildings! They can’t put out those fires.” I was incensed--angry and sad.

.

Although I know the code of firefighters, I was still infuriated that they followed it into such danger. I projected my own relationship with Michael onto their situation until I realized the true source of my fear. There was no separation between “us” and “them.” All firefighters believe in one thing: “To bring each other home safe to our families.”

.

What happened in New York was felt across the world, but I witnessed it first-hand in my husband’s anxious pacing, footsteps. He was ready to go, waiting for the telephone call that would mobilize him. That call never came, although some Salt Lake County firefighters were sent to New York. His job was to stay out and cover home base.

.

I finally received the answer to my demands for more information on the building’s structure, about the architect. It was aired on PBS about nine months later. We were in Chicago, visiting friends and family. The fear of tall buildings coming under attack was still very fresh in everyone’s heart. Chicago has the tallest building in the United States and we were hearing about precautionary procedures and structural integrity--very different information than what we were used to getting as tourists on our earlier visits. People here were not at ease.

.

It was not until I heard the story of the “Six (firefighters) from Ladder Company 6” and their guardian angel, Josephine, that I could begin to release my anger toward the fire chiefs who orchestrated the rescue efforts on that fateful day.

.

I had read about the story first, then saw a TV interview with the firefighters and Josephine. I remember snickering at their obvious discomfort with the interviewer’s efforts to make them admit they were heroes. Six men, each carrying over a hundred pounds of equipment, entered the building from which everyone else was escaping. They found Josephine, a sixty-year-old grandmother, inside the stairwell of the north tower. She had been on the seventy-third floor and had trudged down sixty stories before she sank down, exhausted. The six firefighters had reached the twenty-seventh floor, four levels past Josephine, when they heard the south tower fall. They turned to retreat and stopped where Josephine had slumped to the steps.

.

One of the firefighters hooked Josephine’s arm over his shoulders while he put his arm around her waist to guide her down the stairs. He encouraged her: “Josephine, your kids and your grandkids want you home today. We’ve got to keep moving!” The progress was extremely slow, however. The threat of the building collapsing loomed large in their minds. On the fourth floor, Josephine stopped, gasping, “That’s it. I can’t go anymore.”

.

That’s when the tower went down. Hearing the rumbling, like an approaching train running full force, the firefighter who had been guiding Josephine calmly told her, “Josephine, I’m going to place you in this doorway and shield you with my body.” He did, feeling the floors below them give way and the many floors above them crushing down. The only pocket that survived, walls intact, in the north tower of stairwell B was between the second and the fourth floor. After six hours, all six men from Ladder Company 6 and Josephine were rescued.

.

Rescuing people is part of the job. Michael is a paramedic, too, and many of his calls are medical ones. When he rescued an unconscious six-year-old found hiding in a closet from a fire and was able to revive her, he considered that day to be a pretty good one, but he keeps it in perspective. This is what he does. This is his job.

.

When a fellow firefighter is in danger, his peers exert the same amount of effort to rescue him, but there is a subtle shift in perspective. Michael has often referred to the fire department as a group of men and women who are bound together by an unspoken oath: “If a firefighter is down, everyone bands together to lift him or her up. It’s our job to bring everyone home safe to our families.”

.

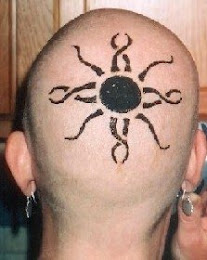

When Michael and I were going through our cancer marathon, this unspoken code went into effect immediately, much of it without our awareness. There are 380 firefighters in the department. All of them heard the news. Michael works closely with about fifty of them. Over a period of four months, twenty firefighters shaved their heads honoring their friend Michael, honoring him honoring me. “If one of us is bald, then we’re all bald.”

.

A friend told us about a firefighter who had the most adorable set of curls atop of his head. “They’re magic,” his wife would say. When everyone around him started shaving, he thought he should, at the very least, talk to his wife about it. Her reply was simple: “I love your curls, but you can shave them off for your friend.”

.

About a week after the bald party, Michael was filling out paperwork at the station when one of his buddies walked up and handed him a check for five hundred dollars. Civil servants typically don’t have large bank accounts. A lot of firefighters have the job as their passion but actually have to hold down a second job to pay the bills. Michael wasn’t sure how to respond, but he understood it. “A fellow firefighter is down, and we need to lift him up.”

.

There are 300 million people in the United States and only 1 million firefighters (70% of them are volunteer), all of them rotating in shifts. When they’re in sync, they can silently move together, matching motion to assist strangers, bringing them out of burning buildings, stabilizing them, preventing them from dying, sending them off in the ambulance, and turning to the next one. It’s a dance, a movement, that occurs without speech because they know each other so very well. I‘ve heard Michael say, “We may never have the opportunity to share a beer together or to shoot a game of pool, but we’re all connected just the same, in this common space in time.”

.

Last week we attended the annual firefighters’ banquet. Two of the three platoons were in attendance, everyone in formal blues. These guys and gals never see each other all in the same place unless there is a huge fire. “It’s like a reunion,” Michael says, happy to see everyone. What I didn’t expect was the attention that I received. From the administrative assistant to the chief and everyone ranked in between, I was receiving many inquiries about how I was doing. My hair got lots of attention. “Look at all that hair!” and “I haven’t see you two since you were both bald!” Time hadn’t passed for many of these people. Time had stopped for them and we were frozen in it. The evening was filled with hearty handshakes and belly laughs, but it was the connection--being able to close this particular chapter for this department--that was most memorable for me. I left feeling honored and blessed.

.

In the end, Michael’s adventure was separate from mine. It included all of these people whom I will seldom meet, many others I will never meet. Hundreds of people hear the news, make inquiries, and continue to keep us in their prayers.

.

Once, when Michael and I were feeling brave, I asked, “If we had to do it all again, could we?” It was a difficult question for both of us, triggering way too many emotions.

.

“If you need to cross over difficult waters, I would build the bridge,” he finally said to me. “I don’t question it. I don’t. It is just the thing that needs to be done. I would do that for you.”

We sat close together, quiet for a long time. I finally said, “I don’t want to go through this experience again, but I know I could, with you by my side.”

.

Like the firefighters in stairwell B of the World Trade Center, remaining together to save one, before the world came roaring down, “I’m going to lay my body over you to shield you, to protect

you...”

.

Michael and I felt this protection, given by the department, his platoon, and each other.

Simply beautiful.

ReplyDelete