Wednesday, January 18, 2012

Saturday, September 10, 2011

Firefighters

.

“I will never allow personal feelings, nor danger to self, deter me from my responsibilities as a firefighter”

-Firefighter Code of Ethics

.

When your life takes a sudden turn and the unexpected lies before you, the simplest of questions appear overwhelming and relying on others for assistance becomes a temporary way of living. It’s foreign ground. Only trust in the guidance sustains you.

.

To understand a firefighter completely and not be one yourself means you’re married to one or pretty darn close to one. Michael considers it an honor to be a firefighter, and I can do nothing but to honor him in discovering and living his passion. Firefighters are a complicated breed. Their common features extend beyond state lines and even national borders. But the thing is--the very thing that drives you nuts about them--is also that thing that makes you love them. Michael is great at what he does; yet he, himself, would never admit to anything more than being just one of the guys within this group.

.

I started anticipating the events of September 11, 2001, about six months before it happened; about four years before cancer would hit our family. Everything came in the form of dreams up until August. Then a terrible sadness started hitting me in the middle of the day, with no apparent trigger. I would be driving and find myself needing to pull over because I couldn’t see through my tears. The wave of emotion would last a few minutes, and then I could carry on with the rest of my day.

.

Benjamin was three and Abigail, one, when the towers fell. I had slept in that morning, something I never did. I woke up when Michael came home, still in uniform from all-night duty. “There has been a terrible accident.” He was almost stuttering. “They think a small plane has hit one of the twin towers in New York.” He was gesturing, his hands needing a task. He actually started signing “accident” and “plane.”

.

Later, the facts became clearer, the horror documented in every media format on earth. I found myself clinging to specific stories. “I want to know how the buildings were built! Why did the chiefs send those firefighters up into those buildings? Planes have hit those buildings! They can’t put out those fires.” I was incensed--angry and sad.

.

Although I know the code of firefighters, I was still infuriated that they followed it into such danger. I projected my own relationship with Michael onto their situation until I realized the true source of my fear. There was no separation between “us” and “them.” All firefighters believe in one thing: “To bring each other home safe to our families.”

.

What happened in New York was felt across the world, but I witnessed it first-hand in my husband’s anxious pacing, footsteps. He was ready to go, waiting for the telephone call that would mobilize him. That call never came, although some Salt Lake County firefighters were sent to New York. His job was to stay out and cover home base.

.

I finally received the answer to my demands for more information on the building’s structure, about the architect. It was aired on PBS about nine months later. We were in Chicago, visiting friends and family. The fear of tall buildings coming under attack was still very fresh in everyone’s heart. Chicago has the tallest building in the United States and we were hearing about precautionary procedures and structural integrity--very different information than what we were used to getting as tourists on our earlier visits. People here were not at ease.

.

It was not until I heard the story of the “Six (firefighters) from Ladder Company 6” and their guardian angel, Josephine, that I could begin to release my anger toward the fire chiefs who orchestrated the rescue efforts on that fateful day.

.

I had read about the story first, then saw a TV interview with the firefighters and Josephine. I remember snickering at their obvious discomfort with the interviewer’s efforts to make them admit they were heroes. Six men, each carrying over a hundred pounds of equipment, entered the building from which everyone else was escaping. They found Josephine, a sixty-year-old grandmother, inside the stairwell of the north tower. She had been on the seventy-third floor and had trudged down sixty stories before she sank down, exhausted. The six firefighters had reached the twenty-seventh floor, four levels past Josephine, when they heard the south tower fall. They turned to retreat and stopped where Josephine had slumped to the steps.

.

One of the firefighters hooked Josephine’s arm over his shoulders while he put his arm around her waist to guide her down the stairs. He encouraged her: “Josephine, your kids and your grandkids want you home today. We’ve got to keep moving!” The progress was extremely slow, however. The threat of the building collapsing loomed large in their minds. On the fourth floor, Josephine stopped, gasping, “That’s it. I can’t go anymore.”

.

That’s when the tower went down. Hearing the rumbling, like an approaching train running full force, the firefighter who had been guiding Josephine calmly told her, “Josephine, I’m going to place you in this doorway and shield you with my body.” He did, feeling the floors below them give way and the many floors above them crushing down. The only pocket that survived, walls intact, in the north tower of stairwell B was between the second and the fourth floor. After six hours, all six men from Ladder Company 6 and Josephine were rescued.

.

Rescuing people is part of the job. Michael is a paramedic, too, and many of his calls are medical ones. When he rescued an unconscious six-year-old found hiding in a closet from a fire and was able to revive her, he considered that day to be a pretty good one, but he keeps it in perspective. This is what he does. This is his job.

.

When a fellow firefighter is in danger, his peers exert the same amount of effort to rescue him, but there is a subtle shift in perspective. Michael has often referred to the fire department as a group of men and women who are bound together by an unspoken oath: “If a firefighter is down, everyone bands together to lift him or her up. It’s our job to bring everyone home safe to our families.”

.

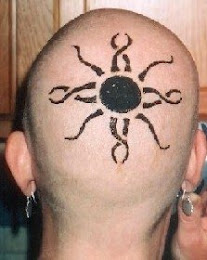

When Michael and I were going through our cancer marathon, this unspoken code went into effect immediately, much of it without our awareness. There are 380 firefighters in the department. All of them heard the news. Michael works closely with about fifty of them. Over a period of four months, twenty firefighters shaved their heads honoring their friend Michael, honoring him honoring me. “If one of us is bald, then we’re all bald.”

.

A friend told us about a firefighter who had the most adorable set of curls atop of his head. “They’re magic,” his wife would say. When everyone around him started shaving, he thought he should, at the very least, talk to his wife about it. Her reply was simple: “I love your curls, but you can shave them off for your friend.”

.

About a week after the bald party, Michael was filling out paperwork at the station when one of his buddies walked up and handed him a check for five hundred dollars. Civil servants typically don’t have large bank accounts. A lot of firefighters have the job as their passion but actually have to hold down a second job to pay the bills. Michael wasn’t sure how to respond, but he understood it. “A fellow firefighter is down, and we need to lift him up.”

.

There are 300 million people in the United States and only 1 million firefighters (70% of them are volunteer), all of them rotating in shifts. When they’re in sync, they can silently move together, matching motion to assist strangers, bringing them out of burning buildings, stabilizing them, preventing them from dying, sending them off in the ambulance, and turning to the next one. It’s a dance, a movement, that occurs without speech because they know each other so very well. I‘ve heard Michael say, “We may never have the opportunity to share a beer together or to shoot a game of pool, but we’re all connected just the same, in this common space in time.”

.

Last week we attended the annual firefighters’ banquet. Two of the three platoons were in attendance, everyone in formal blues. These guys and gals never see each other all in the same place unless there is a huge fire. “It’s like a reunion,” Michael says, happy to see everyone. What I didn’t expect was the attention that I received. From the administrative assistant to the chief and everyone ranked in between, I was receiving many inquiries about how I was doing. My hair got lots of attention. “Look at all that hair!” and “I haven’t see you two since you were both bald!” Time hadn’t passed for many of these people. Time had stopped for them and we were frozen in it. The evening was filled with hearty handshakes and belly laughs, but it was the connection--being able to close this particular chapter for this department--that was most memorable for me. I left feeling honored and blessed.

.

In the end, Michael’s adventure was separate from mine. It included all of these people whom I will seldom meet, many others I will never meet. Hundreds of people hear the news, make inquiries, and continue to keep us in their prayers.

.

Once, when Michael and I were feeling brave, I asked, “If we had to do it all again, could we?” It was a difficult question for both of us, triggering way too many emotions.

.

“If you need to cross over difficult waters, I would build the bridge,” he finally said to me. “I don’t question it. I don’t. It is just the thing that needs to be done. I would do that for you.”

We sat close together, quiet for a long time. I finally said, “I don’t want to go through this experience again, but I know I could, with you by my side.”

.

Like the firefighters in stairwell B of the World Trade Center, remaining together to save one, before the world came roaring down, “I’m going to lay my body over you to shield you, to protect

you...”

.

Michael and I felt this protection, given by the department, his platoon, and each other.

“Good food is like music you can taste, color you can smell. There is excellence all around you. You need only to be aware to stop and savor it.”

-Gusteau, Ratatouille

My friend, TerriLyn died a year ago today.

.

“The way I am feeling is not sustainable” I tell Michael. I’m exhausted and sad and feel an overwhelming emotion of defeat. My brain and my heart are disconnected. Cerebrally, I knew her body was breaking down – “failing” (a word I don’t use often nor like) but regardless of my opinion, this is what it was doing; her body was shutting down.

.

Emotionally, TerriLyn and I still had plans for the future. We were co-survivors and our plans included others, in bringing light to others; sharing the abundance of life even when faced with adversity. I suddenly found myself shutting down too. I had only enough in me to give to my own and to TerriLyn’s family. I spent the daylight hours with mine and evening hours with hers.

.

The last time we spoke outside of the hospital, was in a restaurant. This is a fitting setting for our meeting. She was greeted warmly by our waitress as they discussed TerriLyn’s favorite items on the menu. They shared a communication encrypted with ‘foodisms’ I was unfamiliar with.

.

“Would you like that sauce…” The waitress asked without completing her question.

.

“I would. Is it sweet like the…” TerriLyn responded with a similar incompletion.

.

“As always, we’ll serve it warm - just as you like it – with a side order of…”

.

“Perfect!” TerriLyn did not need her to finish the food order.

.

I was at a loss and eager to see just what was going to be delivered! I’ve always admired these connections TerriLyn had with people. If the rest of the world operated in a ‘Six Degrees of Separation’, then TerriLyn operated in a world separated by only four degrees.

.

But now she is gone and the feeling I am experiencing is not sustainable.

.

My ‘M.O.’ is typically to put my feelings into something tangible; a result in action, rather than stewing. So, I move my body. I practice yoga to literally move the energy of emotion around inside. I hike so that I can expel breath from my body. I laugh during funny movies so that I can feel ‘lightness’ again. Yet, I find myself returning back to my feelings that are not sustainable.

.

“Ugh!” I express with frustration.

.

I schedule myself for some body work with my friend, Carolyn. Carolyn had the opportunity to work on TerriLyn’s body while exchanging stories that bonded them to certain common life experiences. Once again, the heart strings of TerriLyn had hooked another soul. Carolyn, lovingly, made herself available for me.

.

I turn to the lessons that I have learned.

.

When I began writing this book, TerriLyn and I had plans to write it together. We would meet weekly at a coffee shop to swap stories and devise a Lesson Plan, so to speak. We would make notes about what helped us to face the challenges that coincide with surgeries, chemotherapy, radiation, and publicly venturing out into the world completely bald. We shared experiences that differed and those that were similar, but we always ended in the same place: The bottom line to this Cancer Adventure of ours, and perhaps for others too, relied on one very important quality – Humor.

.

As food establishments consistently provided us with the perfect venue for creativity and the exchange of personal experiences, we shared what we knew to be true to our own sustainability: laughter. Somehow, instinctively, we each knew that we would drown in our own sorrow if we could not locate this place in our heart.

.

TerriLyn’s sister, Julie, spoke at her funeral. Once again, a wave of laughter bathed the room of 500-plus of friends and family members as Julie revealed childhood events consistent with the person that I had come to know as my friend. She told a story about TL’s life in Boston where she worked as a barista at a coffee cart (TL is one of the names her family uses for her). She had traveled to Boston for a bicycle seeking adventure. She was indoctrinated to her new home and place of adventure when her bike was stolen shortly after her arrival. Her parents, wanting to support their daughter, bought her a car. A car in Boston can be a great thing, until you need to park it. TerriLyn had received so many parking tickets in one year that she donned all of them for a Halloween costume and arrived at her party as one big parking ticket! And then the car was stolen.

.

Her Boston adventure was well on its way when she met two regular coffee customers who took TerriLyn under their wing, showing her some of the marvels of the east coast thereby muting some of the Boston drama. They opened up their Maine cabin to TL enabling her to work as a ski instructor for one winter; their friendship grew stronger and, once again, TerriLyn had hooked her heart strings into the hearts of this couple. As Julie relayed this Boston Adventure, this couple had not known the impact that they, themselves, had made upon TerriLyn’s life.

.

Gary, TerriLyn’s older brother spoke about the family humor gene living large in his own childhood memory. Recalling big brother stroller rides with TL as the baby passenger, atypical to any OSHA standards and afternoon football practices with their eldest brother, both boys completely geared-up and TL only in her PJs. Sitting in the audience amongst my friends, my emotions waxing and waning, riding my roller coaster of feelings so abundantly, I actually became concerned that I would get to a place where I would be feeling too much.

.

Gary closed his childhood tormenting stories of his younger sister with an endearing event that occurred to him only recently. Gary lives and works in his hometown of Seattle, Washington. He relayed to all of the moist eyes in the room his encounter with a man who lives with a disability so severe that it impedes his walking journey to work each morning; and yet, this man chooses to make that journey each day. Gary thought he was younger than himself, but it was difficult to fully tell as his physical stature was so badly bent and his eyes held years of living in a body that half-worked. Being rainy Seattle, Gary often stops when he sees this man to offer him a car ride to work. Occasionally he takes Gary up on his offer.

.

On one of these rainy days when Gary and this man shared a fairly silent ride, TL’s brother initiated the conversation with morning small talk, commenting on the weather, asking questions about this man’s job, etc. When Gary had forgotten this man’s name, he offered his own name of Gary Folkman first before inquiring again. He said his name was Sam and then paused when he heard Gary’s last name. Sam asked, “Are you related to TerriLyn Folkman?” Gary, somewhat surprised, and then, perhaps later, not, responded, “Yes. She is my sister.” Sam readjusted in his seat and then looked at Gary who was driving his car, “She was the only one who treated me with any kindness and respect when we were in High School together.”

.

* * * * * * *

.

I turn to my teachings of yoga. In my attempt to make sense of this particular ending of my meetings with TerriLyn I cannot honestly say that my relationship with her has ended.

The Yoga Nataraj is a statue that depicts Shiva, a Hindu deity, as a dancer with four arms. The dance refers to the constant cycle of birth and death, sustaining and evolving, which happens with all things. We set ourselves up for disappointment if we attach ourselves to any part of this cycle and lose sight that everything is in a constant flux of change. It's like trying to enjoy the scenic view while riding the Scrambler, that diabolic amusement park ride designed to spin you mercilessly in circles, eventually scrambling your brain, or making you puke, or both. The Nataraj suggests that everything is turning, changing as we speak. Just as things are dying, something else is being born. Opening up the heart to reveal something new –

I’m sitting at the computer and writing the words, but TerriLyn is here with me.

Sunday, November 7, 2010

The Bald Party

--Brother David Steindl-Rast

My best friend, my husband, Michael, went first. He wouldn’t have missed attending out of “shear” support--and the tequila, of course. When Michael’s skull emerged from under his brown curly locks, we compared the results critically. I had decided that my head-shape would better suit baldness than would Michael’s. His firefighting buddies already called him “Bert,” after the Sesame Street character with the long rectangular face. Baldness would only make Michael’s head look more rectangular.

.

Would I fare better in the hidden scars department? I stared in surprise at a jagged “Harry Potter” lightning-bolt, pink scar on the back of Michael’s head. “How did you get that scar, honey?” I inquired.

.

“I was about eight years old and had two cats who liked to sleep on my bed. One day, they were each sleeping on opposite ends. I decided it would be a good plan to jump in just the right spot, somewhere near center, to make the cats pop up.”

.

Everybody was listening, grinning, able to tell that this story was going to be just awful.

“My idea was that the cats would shoot up from the bed and actually pass in mid-air, then plop down on the other end. It was a great plan! The only problem was, I had forgotten that this was the bottom bunk. So I jumped on the bed”--everyone winced in sympathy--” and jammed my head against the metal frame of the upper bunk! Blood squirted everywhere!”

.

Obviously, Michael had survived just fine, but I couldn’t stop myself: “What happened next?”

“Mom was twelve doors down at the neighbor’s, having a cigarette. My sister, Pam, called the neighbor. She was hysterical, but the neighbor told Mom that I had just bumped my head.” Michael was the youngest of four, and the only boy, so his mother had developed a less intense concern for his health than she had held toward her previous children. “My mom took her time walking home. When she finally arrived, she met me covered with blood and trying to calm down Pam.” He pauses with a smirk, thinking back.

.

I was trying to count the stitches running along the puckered scar.

.

“Eight,” he said before I could finish.

.

Everybody picked up a glass, and the stories kept coming--childhood memories about hair, disaster, and survival. More and more people turned their heads to the shears that night.

This night was a response to my oncologist’s suggestion, “Take control of the hair loss. Shave your head,” she advised me. “If you don’t take control of the cancer, the cancer will take control of you.” I was a forty-four year old mother of two young children, I decided right then and there to do exactly what my doctor suggested.

.

I telephoned my friend Tina and invited her to my “Going Bald” Party. She was a blessing, scheduling play dates for my kids and organizing meals following chemo sessions. But this step took the whole cancer adventure to another level. Cancer was not going to be invisible anymore. Before, I could hide the drainage tube and the scar under loose tops, but not baldness. Even without chemo-induced menopause, I didn’t tolerate heat well; the idea of a wig, July sunshine, and hot-flashes was too much. Bald would have to be beautiful.

.

I could hear some hesitant sorrow in Tina’s voice, but I wouldn’t go there. This was going be bald with a bang--tequila, beer, food . . . Tina was beginning to get into it. The idea: We’d all shave our heads! The guest list grew. Family, of course. Friends who were almost family. Friend-friends.

.

“I’m going to have a Bald Party--eating, drinking, dancing; and we’ll all shave our heads. You can too!”

.

Which friends would say, “Great idea, Amy! What time?” Which ones would say, “Who’s this again?”

.

I considered my children’s reactions. My seven-year-old son Benjamin enjoyed a good party. He’d be okay. The key was my own attitude: I showed no apprehension. If I embraced baldness with the same level of acceptance as surgery, Benjamin and I would both be okay.

.

With four-year-old daughter Abigail it was different. She woke up crying one night, while party plans were in full swing. As we cuddled her, she sobbed, “I cannot have a bald teacher! Ms. Terry cannot be bald, too! All of the kids will laugh at me. I have bald parents, but I cannot have a bald teacher!”

.

At the time, our children attended a cooperative preschool where parents had to volunteer for a number of hours per week. Terry, a gifted teacher, had taught Benjamin for two years and was in her second year of teaching Abigail, so she knew our family well. She was used to getting calls at home.

.

“Terry,” I announced, “we need to come up with a lesson plan about hair, and we need it for tomorrow.” Terry listened, asked a couple of questions, and instantly devised a plan to alleviate Abigail’s terror of being surrounded by the bald adults she would have to explain to her friends. Terry swooped through her house, seizing photos of herself with various lengths of hair, which she would show to the children the next day, as a lesson that hair-length doesn’t change the basic person.

.

Michael assisted by suggesting a short cartoon about a jack-a-lope and a sheep who gets sheared. The sheep is embarrassed to show his pink hide, afraid he’ll be laughed at. But the wise jack-a-lope tells the sheep that he has a “pink kink in the way he thinks.” Instead, he needs to look at life from a different perspective.

You need to lift your foot up and slam it on down;

and bound, bound, bound and rebound!

The cartoon ends with the sheep hopping and dancing across the desert, as his sheep’s wool begins to grow again.

.

The children loved the cartoon, as they did Terry’s show-and-tell of her growing and shrinking hair. They could see, in each photo, the obvious fact that she was always, still, Ms. Terry.

.

Then, Terry asked them the question: "If very short hair is okay, then wouldn’t no hair be okay, too?"

.

The circle talk which followed among these wise four- and five-year-olds touched my heart. The children would cover their hair with their hands, inspecting the results in the mirror. They would face across the circle at children facing them, and say things like:

.

“I think I look pretty good.”

“I don’t look funny at all.”

“Look! Ms. Terry, if I cover all of my hair, you just see my face. I like my face.”

.

That was the end of Abigail’s night-time sobbing over baldness.

There were twenty of us, the newly bald, by the time the evening ended. Family, fellow firefighters, and friends. At the party, Terry announced that she was going to grow her hair longer for “Locks of Love,” a charity that provides wigs for cancer survivors (locks of hair have to be a minimum of seven inches long). She also swept up the hair from the floor after everyone had been cut, clipped, and shaved.

.

I was neither the first nor the last, but when I took the stool, a silence fell on the laughter and storytelling. Nothing needed to be said. It was simply the reason of our gathering on that rainy evening in the garage. Merb, my hairdresser, did a superb job, giving me a nice clean cut, and then an even better shave. And, some saving grace, my head shape was, indeed, more aesthetically pleasing than Michael’s.

.

Then, when Merb was through with me, she unexpectedly exclaimed, “Oh, hell!” Handing me her razor, she demanded: “Your turn!”

.

Unsure, I inquired, “You want me to shave your head?”

.

“Yep!” she confirmed. “Now, pass the tequila.”

.

Merb has the most amazing blue eyes, so large that they capture your attention immediately. Her eyes are the outward reflection of her heart. Bold, brash, and beautiful. I shaved her head bald that evening wondering about the implications for her future hairdressing referrals: “Try my hair stylist! The bald one.”

.

Benjamin and Michael both have unusually lumpy heads. Somewhere Michael had encountered the science of phrenology--a way of identifying personality traits by the placement and size of skull-lumps. (Brigham Young, the much-married founder of Mormon Utah, is said to have had an enormous bump of “amativeness.”) I looked up phrenological charts, and tried it out, feeling Michael’s skull with my fingertips and palms, discerning enlargements or indentations to predict relationships and typical behavior. Heck! Would it work for assessing prospective marriage partners? Or, as a background check for prospective employment? Could we raise grant money for a scientific study to see if firefighters—breast cancer survivors, too--have similar patterns of head-lumps?

.

It took about four months for my hair to grow back--past chemotherapy, and well into the radiation stage. Michael wasn’t content with the one-time shave; he resolutely remained bald as long as I did. He had about a dozen moles on the top of his head, another secret about his naturally hirsute being laid bare. Every time he shaved--about every three days--he would emerge from the bathroom with tiny scraps of toilet paper sticking to each bloody spot. Although his technique improved with time, I don’t think he ever survived a single week without loss of blood.

.

See why I love him?

Monday, August 30, 2010

Walking Angels

--Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

My friend, TerriLyn, and I often talk about our encounters with “walking angels.” She told me about meeting one in a mall with her nine-year-old daughter, Gabrielle. She was feeling particularly low this day, chemo taking a vicious toll emotionally on her and afflicting her with periodic chemo-induced hot flashes. She was wearing a bandanna over her bald head. Both of them were waiting for something tangible to leap out and yell “Buy me!”

“Perhaps a new pair of earrings?” she half-asked her daughter.

-

It was the second half of her real question: “What would make me feel better right now?”

-

A woman approached TerriLyn and her daughter, face glowing and eyes bright. She seemed familiar, but TerriLyn couldn’t place the face.

-

Involuntarily, she asked, “Do I know you?”

-

“No.” The woman shook her head. “But I just wanted to say that you are looking great!”

-

“Thanks. Thank you very much.” TerriLyn was so stunned that she almost stammered.

-

Then the woman was gone.

-

TerriLyn stood in the aisle looking down at Gabrielle. She ran her hand over her daughter’s hair, then rested her hand on her shoulder. She appeared to be growing taller by the minute. She looked more deeply into her daughter’s face--not surprised, not asking questions, just looking back at her. She glanced down again, feeling a bit lighter than she had before this encounter.

-

“Gabrielle,” she asks, smiling, “Wanna buy some earrings?”

Thursday, May 27, 2010

Letting Go of Pain

A true friend stabs you in the front

--Oscar Wilde

In August 2008, in celebration of three friends who turned fifty, a group of fourteen took a one-week cruise up Alaska’s inside passage. Four amongst us were teenagers, one of whom turned fifteen at sea. The trip marked the first time Michael and I had traveled together without our children since their births. It took careful consideration, coordination, and collaboration. It was significant.

These people are my “Big Chill” group, the name coming from the 1983 movie. Aboard ship we were once again that group of young men and women living in the Haight-Ashbury, Noe Valley, and Castro District of San Francisco in the first half of the 1980s. Our past took place in the midst of an AIDS epidemic, struggles with graduate school, lovers with all preferences of lifestyles, seeking careers and the individual paths that would later define us--or, at least, would define us for a moment of time. We have managed to keep in touch with each other through marriages, lovers, childbirths, and adoptions. We try to see each other once a year and succeed about 50 percent of the time. But this trip required 100 percent participation. We did it, and we were grateful for the week we spent at sea with each other.

The days were filled with adventures. We all ventured off the boat in different directions: ocean kayaking, cycling to blue glaciers, dog sledding, helicopter rides, train rides to sites that Jack London had used as settings for his stories. Between the fourteen of us, we covered a lot of ground.

Our group dinners every night at 8:00 P.M. celebrated the events of the day, and our table of ten was always the last to leave so the tolerant wait staff could clear it. The volume of our laughter consistently exceeded acceptable decibel levels, but not once were we reprimanded. It was the time spent around the table that meant the most to me. These friends had supported Michael and me through our cancer adventure.

When it came time to sign up for the “On Deck for the Cure” walk around the ship, we all walked or ran at our own pace. With whales swimming off our port bow in the still, blue-gray waters, I could think of no better place to let go of my pain. In releasing remnants of whatever I held onto from the past three-plus years, I gained more in love and faith of these friendships sustained. It was this group who showed me,

Monday, March 22, 2010

Meeting Michael

I’ve gone through life making a billion decisions, not always knowing what lay breath to any particular one. Sometimes, decisions don’t seem to lead me where I intend. Then there are times when everything falls into place, and I find myself blanketed in gratitude for making those very uncertain decisions, because they had led me to that place of welcomed grace, that loving place of balance and benevolence. Nevertheless, I’ve found that if my intentions were toward love, pure and simple, then, that’s what I’ll inevitably find.

When I was once looking for help, I found Michael, my husband—the love of my life. When I first met him, I was a high-school teacher for the Deaf and hard of hearing in California. As part of my curriculum, I introduced my students to one of my own great passions: rock-climbing. They weren’t motivated by the typical teenage need for thrills or attention-seeking. These were youth who needed—excuse the expression—a “crash” course in confidence. They had chosen rock-climbing out of a smorgasbord of choices, and they were all on-board to give it a go.

I had been turned away from three different rock-climbing gyms, and their instructors all reported back to me the same excuse: “We feel the ‘situation’ causes too much liability.”

I became more persistent. From my own experience with rock-climbing, I was well aware of its confidence-boosting benefits. My students came from many cultures--one of these cultures being Deaf. More often than not, students’ parents never learned American Sign Language; and parents would come to rely on their teachers and interpreters for all of the life lessons their children received. I had Vietnamese, Laotian, African American/Cambodian, Taiwanese, and Hispanic students. Students’ parents spoke their native language at home. If able, they would speak English when they were meeting me at school. Most parents saw deafness as a disability rather than a cultural difference.

The combination of this perspective on deafness, combined with traditions carried from their native countries, often left their children with poor self-esteem that, by high school, resulted in many poor and uninformed choices. One of my students was raped because she got into the car of a stranger who was good-looking and smiling. Another became pregnant for much the same reason. Two of my students stood on the verge of getting kicked out of their homes, and all of these choices were linked to a lack of communication and education.

I managed to persuade all of the parents to sign permission slips so I could take them on a city adventure--climb a wall and build some confidence. It was my desire that this experience would eventually lead to their honoring themselves, which would lead to making better choices. The Deaf community was more than willing to cooperate with me. They assisted me with organizing interpreters and even found experienced rock-climbing instructors who were Deaf. The hearing community gave me the most difficult time!

It was 1991, and indoor climbing gyms, though on the verge of becoming popular, were not yet abundant. My Deaf students were still considered a “challenging” group. The sport of indoor-climbing and access to the sport were new; so were the rules that governed the walls. Furthermore, few supervisors and store owners knew what the rules were. I understood why they erred on the side of caution. I just didn’t agree with them.

Michael’s position as rock-climbing manager at the Sport Chalet in Huntington Beach offered him some latitude for creativity. For example, he had designed a climbing wall on the outside of the building, rather than inside, which was the typical placement. He had nine routes of various difficulties enclosed in a fenced-off area in the back. This climbing wall drew customers to the shop, making it a win-win situation for everyone.

Michael didn’t hesitate when I asked about lessons for my group of students, instructors and interpreters. What he didn’t tell me, until later, was that he, himself, had been taking sign language courses at the local community college.

We placed one interpreter at the top of the twenty-five foot building, so the climber/student could look up; we placed another at the foot of the wall so the climber/student could look down. This triangulation enabled my students to climb, as well as communicate toward their desired direction. Because both signing and climbing require use of the hands, all students were top-roped, allowing them to let go of the wall and still be supported.

I like to find metaphors in everything, and this one was significant to me. I wanted my students to know, “You can let go of everything for just this moment in time and still be held up. We won’t let you fall. We won’t let you down. Tell us what you need!”

The day was successful in many respects. It marked the beginning of relationships that laid foundations for trust. I was able to take these same students to a YMCA Deaf Camp for five consecutive years following that first rock-climbing experience. I was invited to eat dinner with my students’ families, who were often too poor to feed themselves adequately. I felt honored and cherished to join them, in full Cambodian tradition, on a beautiful mat laid out on the floor of their apartments. Communication barriers persisted, too, but we ate in celebration of our shared belief that we simply must begin somewhere and that sharing food was a way of sharing love.

In my pursuit for a rock-climbing facility for my students I had met my angel: Michael. I had not told him for, at least, two months that I had recognized him instantly as I walked down the aisle of the sporting goods store. I actually had the thought, “Oh, this is the guy for me!” I fell in love with him instinctively. Michael and I married three years after that rock-climbing Saturday afternoon. At our wedding, we included two interpreters (one for the male voice and one for the female voice). The service was on the grounds of the Long Beach Museum of Art, overlooking the ocean. Catalina Island glistened in the distance. We made our vows as the sun slid over the horizon, before our friends, family, and students. Our cake was shaped in the form of a mountain with a bride and a groom (iron, welded by an artist friend) portrayed as rock climbers. The groom (with welded top hat) was belaying his bride (bedecked with a white lace train) to the top of the mountain.

Michael’s best man, during his toast, bestowed on Michael his own title of “Best Man.” There was no man better: a man who was willing to help, to support, to lift up…. “It’s just who he is, because it’s the right thing to be.” And so he is. Michael’s goodness is completely evidenced in his willingness to remain present. Regardless of sacrifices involved, he has never altered his commitment to remaining present. That is my definition of a hero. I have been sure of this since the beginning of our relationship together. We entered the cancer adventure as a unit, each present and ready to accept the challenge of the climb.