From there to here, from here to there,

Funny things are everywhere.--

-Dr. Seuss

When cancer found us, we were living in what I fondly called our “San Francisco house.” Our Salt Lake City home was an old one built just twenty-five feet wide and forty feet deep. You could have a conversation with our neighbor through the bathroom windows. (Thank goodness for our neighbor’s SF modesty!)

.

We loved this house. We worked on the backyard for five years, making it comfortable for entertaining guests. We ate almost every meal there during the summer time. Michael had installed a misting system that lowered the temperature 20 degrees during the hot summer days and early evenings. We had one herb garden and a second tomato garden. We built a swing set with a fort for the children and a two-car garage with a workshop for Michael, and I had my rocking chair glider. This was all that I needed to watch the nature in the yard, feel the breeze, hear the sounds of my family. This was a great place!

We loved this house. We worked on the backyard for five years, making it comfortable for entertaining guests. We ate almost every meal there during the summer time. Michael had installed a misting system that lowered the temperature 20 degrees during the hot summer days and early evenings. We had one herb garden and a second tomato garden. We built a swing set with a fort for the children and a two-car garage with a workshop for Michael, and I had my rocking chair glider. This was all that I needed to watch the nature in the yard, feel the breeze, hear the sounds of my family. This was a great place!

.

One of my favorite spots in the house, however, was my son Benjamin’s room. His room was the size of a large closet. We put a mattress on an elevated platform. Underneath was storage for his toys. Michael built a bookshelf with a bulletin board as a head board. On the very top we built another shelf that held sweet treasure boxes and a night light that twirled around and projected stars upon his walls and ceiling. I painted clouds on a blue sky on the ceiling of his room, to be seen by day, and stuck glow-in-the-dark star stickers, to be seen by night. I painted a city scene with Michael’s fire truck and his station number on it. I painted our home with our whole family, including Mazzie, the dog, and Mildred, the cat, standing beside it. It was three-year-old perfect. Benjamin loved this room and so did I.

One of my favorite spots in the house, however, was my son Benjamin’s room. His room was the size of a large closet. We put a mattress on an elevated platform. Underneath was storage for his toys. Michael built a bookshelf with a bulletin board as a head board. On the very top we built another shelf that held sweet treasure boxes and a night light that twirled around and projected stars upon his walls and ceiling. I painted clouds on a blue sky on the ceiling of his room, to be seen by day, and stuck glow-in-the-dark star stickers, to be seen by night. I painted a city scene with Michael’s fire truck and his station number on it. I painted our home with our whole family, including Mazzie, the dog, and Mildred, the cat, standing beside it. It was three-year-old perfect. Benjamin loved this room and so did I.

.

He had a small window, just two panes, that we upgraded so he could open it safely without any chance of falling out. The open window let cool air in and allowed him to lie on the edge of his bed watching the world go by. These were the moments that I loved best about my son’s relationship with his room and his window.

He had a small window, just two panes, that we upgraded so he could open it safely without any chance of falling out. The open window let cool air in and allowed him to lie on the edge of his bed watching the world go by. These were the moments that I loved best about my son’s relationship with his room and his window.

.

When I asked him what he could see, he would say, “I see our neighbor across the street dancing in the rain. Sometimes I watch our neighbor’s family play football on the grass island in the middle of the wide street. I see kids riding their bikes. I like riding mine. I see cars going by, and Mazzie running back and forth on the sidewalk in front of the house. I love the dragonflies best, Mom. They are spirits from heaven. I think they have chosen our house to fly in front of. I don’t see them anywhere else. . . . They are like Snoopy and the Red Baron diving down and then zooming back up into the sky.”

When I asked him what he could see, he would say, “I see our neighbor across the street dancing in the rain. Sometimes I watch our neighbor’s family play football on the grass island in the middle of the wide street. I see kids riding their bikes. I like riding mine. I see cars going by, and Mazzie running back and forth on the sidewalk in front of the house. I love the dragonflies best, Mom. They are spirits from heaven. I think they have chosen our house to fly in front of. I don’t see them anywhere else. . . . They are like Snoopy and the Red Baron diving down and then zooming back up into the sky.”

.

The window was very small, but, from Benjamin’s perspective, it was the portal to the world outside. I loved watching the sunset fall on his face and his auburn hair as he watched the kids on the block turn in toward their homes for the night.

The window was very small, but, from Benjamin’s perspective, it was the portal to the world outside. I loved watching the sunset fall on his face and his auburn hair as he watched the kids on the block turn in toward their homes for the night.

.

Cancer and chemo occurred while living in this house. By the time I started radiation therapy in September, 2005, we had moved to a new home in our new neighborhood. Recently, I took Benjamin back to our old home and asked him to look at his window.

Cancer and chemo occurred while living in this house. By the time I started radiation therapy in September, 2005, we had moved to a new home in our new neighborhood. Recently, I took Benjamin back to our old home and asked him to look at his window.

.

“Wow. It’s so tiny!” he marveled, pointing up at the house.

“Wow. It’s so tiny!” he marveled, pointing up at the house.

.

“You lived in that room from the time you were three until we moved out when you were seven. You loved that room, do you remember?”

“You lived in that room from the time you were three until we moved out when you were seven. You loved that room, do you remember?”

.

He nods, still thinking aloud, he adds, “I remember Ben T., asking me, ‘Is your mom okay? Has she grown any hair yet?’ I remember that he would ask me a lot. He is my best friend and I think he was worried about me.” I can see that he is thinking about this time.

He nods, still thinking aloud, he adds, “I remember Ben T., asking me, ‘Is your mom okay? Has she grown any hair yet?’ I remember that he would ask me a lot. He is my best friend and I think he was worried about me.” I can see that he is thinking about this time.

.

I get a little nervous about how different we looked when we left, our bald heads and all.

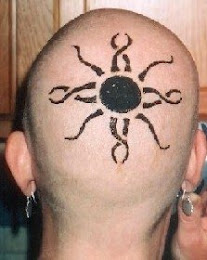

But Benjamin is sharing his way of remembering: “It was funny having Dad have a bald head, too. Dad always makes funny faces. He crosses his eyes and does something funny with his mouth. I remember getting a black marker and drawing on the back of his head. I drew a face on the back of his head. Our friend, Lu, drew a sheep on the top of her head.” He’s cracking himself up now. “I wanted you to have hair again, but not Dad. It was fun to draw faces on the back of his head.”

I get a little nervous about how different we looked when we left, our bald heads and all.

But Benjamin is sharing his way of remembering: “It was funny having Dad have a bald head, too. Dad always makes funny faces. He crosses his eyes and does something funny with his mouth. I remember getting a black marker and drawing on the back of his head. I drew a face on the back of his head. Our friend, Lu, drew a sheep on the top of her head.” He’s cracking himself up now. “I wanted you to have hair again, but not Dad. It was fun to draw faces on the back of his head.”

.

“I remember you lost your mind for real, Mom.” He elbows me in the ribs. “You had chemo brain and we needed to get you a board to remember things.” There was an aquarium at the cancer center that had a fish that looked like the absent-minded character Dory from the movie Nemo. “That was funny. Mommy was Dory.”

“I remember you lost your mind for real, Mom.” He elbows me in the ribs. “You had chemo brain and we needed to get you a board to remember things.” There was an aquarium at the cancer center that had a fish that looked like the absent-minded character Dory from the movie Nemo. “That was funny. Mommy was Dory.”

.

He then started running lines from the movie with me. “Why are you following me?” Dory would ask. He laughs at himself. I laugh with him, because everything he says is absolutely true.

He then started running lines from the movie with me. “Why are you following me?” Dory would ask. He laughs at himself. I laugh with him, because everything he says is absolutely true.

.

“I remember the dogs that would visit while you had tubes in your arm. I remember seeing other people getting chemo, too.” He says these things, trying to make a connection in his own memory bank of experiences. I feel that if he can do this, then the memories will magically become ‘okay’ for him.

“I remember the dogs that would visit while you had tubes in your arm. I remember seeing other people getting chemo, too.” He says these things, trying to make a connection in his own memory bank of experiences. I feel that if he can do this, then the memories will magically become ‘okay’ for him.

.

“I remember when I got my tonsils out.” He’d been nine for that operation. “It hurt like getting tubes in the hand--like what you got.” He pauses, then smiles, “Oh, yeah, and I got to ride in a wheelchair. That was awesome.”

“I remember when I got my tonsils out.” He’d been nine for that operation. “It hurt like getting tubes in the hand--like what you got.” He pauses, then smiles, “Oh, yeah, and I got to ride in a wheelchair. That was awesome.”

.

Cancer shifted all of our perspectives that spring, summer, and fall. Unexpectedly, we found a house that could fit our growing bodies that brought all our activities but Michael’s fire station into one neighborhood: our home was close to our school and also near my hospital. In addition, it gave Benjamin a larger window and it’s the house we still live in.

Cancer shifted all of our perspectives that spring, summer, and fall. Unexpectedly, we found a house that could fit our growing bodies that brought all our activities but Michael’s fire station into one neighborhood: our home was close to our school and also near my hospital. In addition, it gave Benjamin a larger window and it’s the house we still live in.

.

We moved when he was almost eight, and now his bedroom window has sixteen panes through which he sees sunrises rather than sunsets. Mountains, rather than street intersections. He can view the backyard and things that are private to him. He tells me, “I’ll be able to see the seasons change from this window.” His perspective seems to be more in balance with this new portal to the world. He tells me not just about what he sees but about what they mean--his interpretation of what the world is. “It’s odd, Mom. A pleasant day can equal bad dreams and then a bad day can equal pleasant dreams.”

We moved when he was almost eight, and now his bedroom window has sixteen panes through which he sees sunrises rather than sunsets. Mountains, rather than street intersections. He can view the backyard and things that are private to him. He tells me, “I’ll be able to see the seasons change from this window.” His perspective seems to be more in balance with this new portal to the world. He tells me not just about what he sees but about what they mean--his interpretation of what the world is. “It’s odd, Mom. A pleasant day can equal bad dreams and then a bad day can equal pleasant dreams.”

.

How quickly he shifted, I think. It’s been just a matter of months. . . but suddenly, I realize what lies behind his meaning, as if a horse’s blinders were finally removed. Benjamin was saying that his view had widened--that he could see from a broader scope. There is still wonderment and magic in his sight and in his mind, but he is no longer limited to just the differences of “what is” compared to “what can be.”

How quickly he shifted, I think. It’s been just a matter of months. . . but suddenly, I realize what lies behind his meaning, as if a horse’s blinders were finally removed. Benjamin was saying that his view had widened--that he could see from a broader scope. There is still wonderment and magic in his sight and in his mind, but he is no longer limited to just the differences of “what is” compared to “what can be.”

.