The Bald Party

It is not joy that makes us grateful; it is gratitude that makes us joyful.

--Brother David Steindl-Rast

.--Brother David Steindl-Rast

My best friend, my husband, Michael, went first. He wouldn’t have missed attending out of “shear” support--and the tequila, of course. When Michael’s skull emerged from under his brown curly locks, we compared the results critically. I had decided that my head-shape would better suit baldness than would Michael’s. His firefighting buddies already called him “Bert,” after the Sesame Street character with the long rectangular face. Baldness would only make Michael’s head look more rectangular.

.

Would I fare better in the hidden scars department? I stared in surprise at a jagged “Harry Potter” lightning-bolt, pink scar on the back of Michael’s head. “How did you get that scar, honey?” I inquired.

.

“I was about eight years old and had two cats who liked to sleep on my bed. One day, they were each sleeping on opposite ends. I decided it would be a good plan to jump in just the right spot, somewhere near center, to make the cats pop up.”

.

Everybody was listening, grinning, able to tell that this story was going to be just awful.

“My idea was that the cats would shoot up from the bed and actually pass in mid-air, then plop down on the other end. It was a great plan! The only problem was, I had forgotten that this was the bottom bunk. So I jumped on the bed”--everyone winced in sympathy--” and jammed my head against the metal frame of the upper bunk! Blood squirted everywhere!”

.

Obviously, Michael had survived just fine, but I couldn’t stop myself: “What happened next?”

“Mom was twelve doors down at the neighbor’s, having a cigarette. My sister, Pam, called the neighbor. She was hysterical, but the neighbor told Mom that I had just bumped my head.” Michael was the youngest of four, and the only boy, so his mother had developed a less intense concern for his health than she had held toward her previous children. “My mom took her time walking home. When she finally arrived, she met me covered with blood and trying to calm down Pam.” He pauses with a smirk, thinking back.

.

I was trying to count the stitches running along the puckered scar.

.

“Eight,” he said before I could finish.

.

Everybody picked up a glass, and the stories kept coming--childhood memories about hair, disaster, and survival. More and more people turned their heads to the shears that night.

This night was a response to my oncologist’s suggestion, “Take control of the hair loss. Shave your head,” she advised me. “If you don’t take control of the cancer, the cancer will take control of you.” I was a forty-four year old mother of two young children, I decided right then and there to do exactly what my doctor suggested.

.

I telephoned my friend Tina and invited her to my “Going Bald” Party. She was a blessing, scheduling play dates for my kids and organizing meals following chemo sessions. But this step took the whole cancer adventure to another level. Cancer was not going to be invisible anymore. Before, I could hide the drainage tube and the scar under loose tops, but not baldness. Even without chemo-induced menopause, I didn’t tolerate heat well; the idea of a wig, July sunshine, and hot-flashes was too much. Bald would have to be beautiful.

.

I could hear some hesitant sorrow in Tina’s voice, but I wouldn’t go there. This was going be bald with a bang--tequila, beer, food . . . Tina was beginning to get into it. The idea: We’d all shave our heads! The guest list grew. Family, of course. Friends who were almost family. Friend-friends.

.

“I’m going to have a Bald Party--eating, drinking, dancing; and we’ll all shave our heads. You can too!”

.

Which friends would say, “Great idea, Amy! What time?” Which ones would say, “Who’s this again?”

.

I considered my children’s reactions. My seven-year-old son Benjamin enjoyed a good party. He’d be okay. The key was my own attitude: I showed no apprehension. If I embraced baldness with the same level of acceptance as surgery, Benjamin and I would both be okay.

.

With four-year-old daughter Abigail it was different. She woke up crying one night, while party plans were in full swing. As we cuddled her, she sobbed, “I cannot have a bald teacher! Ms. Terry cannot be bald, too! All of the kids will laugh at me. I have bald parents, but I cannot have a bald teacher!”

.

At the time, our children attended a cooperative preschool where parents had to volunteer for a number of hours per week. Terry, a gifted teacher, had taught Benjamin for two years and was in her second year of teaching Abigail, so she knew our family well. She was used to getting calls at home.

.

“Terry,” I announced, “we need to come up with a lesson plan about hair, and we need it for tomorrow.” Terry listened, asked a couple of questions, and instantly devised a plan to alleviate Abigail’s terror of being surrounded by the bald adults she would have to explain to her friends. Terry swooped through her house, seizing photos of herself with various lengths of hair, which she would show to the children the next day, as a lesson that hair-length doesn’t change the basic person.

.

Michael assisted by suggesting a short cartoon about a jack-a-lope and a sheep who gets sheared. The sheep is embarrassed to show his pink hide, afraid he’ll be laughed at. But the wise jack-a-lope tells the sheep that he has a “pink kink in the way he thinks.” Instead, he needs to look at life from a different perspective.

.

You need to lift your foot up and slam it on down;

and bound, bound, bound and rebound!

.You need to lift your foot up and slam it on down;

and bound, bound, bound and rebound!

The cartoon ends with the sheep hopping and dancing across the desert, as his sheep’s wool begins to grow again.

.

The children loved the cartoon, as they did Terry’s show-and-tell of her growing and shrinking hair. They could see, in each photo, the obvious fact that she was always, still, Ms. Terry.

.

Then, Terry asked them the question: "If very short hair is okay, then wouldn’t no hair be okay, too?"

.

The circle talk which followed among these wise four- and five-year-olds touched my heart. The children would cover their hair with their hands, inspecting the results in the mirror. They would face across the circle at children facing them, and say things like:

.

“I think I look pretty good.”

“I don’t look funny at all.”

“Look! Ms. Terry, if I cover all of my hair, you just see my face. I like my face.”

.

That was the end of Abigail’s night-time sobbing over baldness.

There were twenty of us, the newly bald, by the time the evening ended. Family, fellow firefighters, and friends. At the party, Terry announced that she was going to grow her hair longer for “Locks of Love,” a charity that provides wigs for cancer survivors (locks of hair have to be a minimum of seven inches long). She also swept up the hair from the floor after everyone had been cut, clipped, and shaved.

.

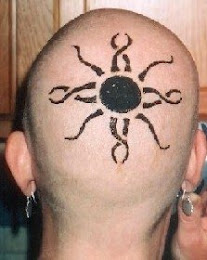

I was neither the first nor the last, but when I took the stool, a silence fell on the laughter and storytelling. Nothing needed to be said. It was simply the reason of our gathering on that rainy evening in the garage. Merb, my hairdresser, did a superb job, giving me a nice clean cut, and then an even better shave. And, some saving grace, my head shape was, indeed, more aesthetically pleasing than Michael’s.

.

Then, when Merb was through with me, she unexpectedly exclaimed, “Oh, hell!” Handing me her razor, she demanded: “Your turn!”

.

Unsure, I inquired, “You want me to shave your head?”

.

“Yep!” she confirmed. “Now, pass the tequila.”

.

Merb has the most amazing blue eyes, so large that they capture your attention immediately. Her eyes are the outward reflection of her heart. Bold, brash, and beautiful. I shaved her head bald that evening wondering about the implications for her future hairdressing referrals: “Try my hair stylist! The bald one.”

.

Benjamin and Michael both have unusually lumpy heads. Somewhere Michael had encountered the science of phrenology--a way of identifying personality traits by the placement and size of skull-lumps. (Brigham Young, the much-married founder of Mormon Utah, is said to have had an enormous bump of “amativeness.”) I looked up phrenological charts, and tried it out, feeling Michael’s skull with my fingertips and palms, discerning enlargements or indentations to predict relationships and typical behavior. Heck! Would it work for assessing prospective marriage partners? Or, as a background check for prospective employment? Could we raise grant money for a scientific study to see if firefighters—breast cancer survivors, too--have similar patterns of head-lumps?

.

It took about four months for my hair to grow back--past chemotherapy, and well into the radiation stage. Michael wasn’t content with the one-time shave; he resolutely remained bald as long as I did. He had about a dozen moles on the top of his head, another secret about his naturally hirsute being laid bare. Every time he shaved--about every three days--he would emerge from the bathroom with tiny scraps of toilet paper sticking to each bloody spot. Although his technique improved with time, I don’t think he ever survived a single week without loss of blood.

.

See why I love him?