Meeting Michael

The best and most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or even touched. They must be felt within the heart.

--Helen Keller

.

I’ve gone through life making a billion decisions, not always knowing what lay breath to any particular one. Sometimes, decisions don’t seem to lead me where I intend. Then there are times when everything falls into place, and I find myself blanketed in gratitude for making those very uncertain decisions, because they had led me to that place of welcomed grace, that loving place of balance and benevolence. Nevertheless, I’ve found that if my intentions were toward love, pure and simple, then, that’s what I’ll inevitably find.

I’ve gone through life making a billion decisions, not always knowing what lay breath to any particular one. Sometimes, decisions don’t seem to lead me where I intend. Then there are times when everything falls into place, and I find myself blanketed in gratitude for making those very uncertain decisions, because they had led me to that place of welcomed grace, that loving place of balance and benevolence. Nevertheless, I’ve found that if my intentions were toward love, pure and simple, then, that’s what I’ll inevitably find.

.

When I was once looking for help, I found Michael, my husband—the love of my life. When I first met him, I was a high-school teacher for the Deaf and hard of hearing in California. As part of my curriculum, I introduced my students to one of my own great passions: rock-climbing. They weren’t motivated by the typical teenage need for thrills or attention-seeking. These were youth who needed—excuse the expression—a “crash” course in confidence. They had chosen rock-climbing out of a smorgasbord of choices, and they were all on-board to give it a go.

When I was once looking for help, I found Michael, my husband—the love of my life. When I first met him, I was a high-school teacher for the Deaf and hard of hearing in California. As part of my curriculum, I introduced my students to one of my own great passions: rock-climbing. They weren’t motivated by the typical teenage need for thrills or attention-seeking. These were youth who needed—excuse the expression—a “crash” course in confidence. They had chosen rock-climbing out of a smorgasbord of choices, and they were all on-board to give it a go.

.

I had been turned away from three different rock-climbing gyms, and their instructors all reported back to me the same excuse: “We feel the ‘situation’ causes too much liability.”

I had been turned away from three different rock-climbing gyms, and their instructors all reported back to me the same excuse: “We feel the ‘situation’ causes too much liability.”

.

I became more persistent. From my own experience with rock-climbing, I was well aware of its confidence-boosting benefits. My students came from many cultures--one of these cultures being Deaf. More often than not, students’ parents never learned American Sign Language; and parents would come to rely on their teachers and interpreters for all of the life lessons their children received. I had Vietnamese, Laotian, African American/Cambodian, Taiwanese, and Hispanic students. Students’ parents spoke their native language at home. If able, they would speak English when they were meeting me at school. Most parents saw deafness as a disability rather than a cultural difference.

I became more persistent. From my own experience with rock-climbing, I was well aware of its confidence-boosting benefits. My students came from many cultures--one of these cultures being Deaf. More often than not, students’ parents never learned American Sign Language; and parents would come to rely on their teachers and interpreters for all of the life lessons their children received. I had Vietnamese, Laotian, African American/Cambodian, Taiwanese, and Hispanic students. Students’ parents spoke their native language at home. If able, they would speak English when they were meeting me at school. Most parents saw deafness as a disability rather than a cultural difference.

.

The combination of this perspective on deafness, combined with traditions carried from their native countries, often left their children with poor self-esteem that, by high school, resulted in many poor and uninformed choices. One of my students was raped because she got into the car of a stranger who was good-looking and smiling. Another became pregnant for much the same reason. Two of my students stood on the verge of getting kicked out of their homes, and all of these choices were linked to a lack of communication and education.

The combination of this perspective on deafness, combined with traditions carried from their native countries, often left their children with poor self-esteem that, by high school, resulted in many poor and uninformed choices. One of my students was raped because she got into the car of a stranger who was good-looking and smiling. Another became pregnant for much the same reason. Two of my students stood on the verge of getting kicked out of their homes, and all of these choices were linked to a lack of communication and education.

.

I managed to persuade all of the parents to sign permission slips so I could take them on a city adventure--climb a wall and build some confidence. It was my desire that this experience would eventually lead to their honoring themselves, which would lead to making better choices. The Deaf community was more than willing to cooperate with me. They assisted me with organizing interpreters and even found experienced rock-climbing instructors who were Deaf. The hearing community gave me the most difficult time!

I managed to persuade all of the parents to sign permission slips so I could take them on a city adventure--climb a wall and build some confidence. It was my desire that this experience would eventually lead to their honoring themselves, which would lead to making better choices. The Deaf community was more than willing to cooperate with me. They assisted me with organizing interpreters and even found experienced rock-climbing instructors who were Deaf. The hearing community gave me the most difficult time!

.

It was 1991, and indoor climbing gyms, though on the verge of becoming popular, were not yet abundant. My Deaf students were still considered a “challenging” group. The sport of indoor-climbing and access to the sport were new; so were the rules that governed the walls. Furthermore, few supervisors and store owners knew what the rules were. I understood why they erred on the side of caution. I just didn’t agree with them.

It was 1991, and indoor climbing gyms, though on the verge of becoming popular, were not yet abundant. My Deaf students were still considered a “challenging” group. The sport of indoor-climbing and access to the sport were new; so were the rules that governed the walls. Furthermore, few supervisors and store owners knew what the rules were. I understood why they erred on the side of caution. I just didn’t agree with them.

.

Michael’s position as rock-climbing manager at the Sport Chalet in Huntington Beach offered him some latitude for creativity. For example, he had designed a climbing wall on the outside of the building, rather than inside, which was the typical placement. He had nine routes of various difficulties enclosed in a fenced-off area in the back. This climbing wall drew customers to the shop, making it a win-win situation for everyone.

Michael’s position as rock-climbing manager at the Sport Chalet in Huntington Beach offered him some latitude for creativity. For example, he had designed a climbing wall on the outside of the building, rather than inside, which was the typical placement. He had nine routes of various difficulties enclosed in a fenced-off area in the back. This climbing wall drew customers to the shop, making it a win-win situation for everyone.

.

Michael didn’t hesitate when I asked about lessons for my group of students, instructors and interpreters. What he didn’t tell me, until later, was that he, himself, had been taking sign language courses at the local community college.

Michael didn’t hesitate when I asked about lessons for my group of students, instructors and interpreters. What he didn’t tell me, until later, was that he, himself, had been taking sign language courses at the local community college.

.

We placed one interpreter at the top of the twenty-five foot building, so the climber/student could look up; we placed another at the foot of the wall so the climber/student could look down. This triangulation enabled my students to climb, as well as communicate toward their desired direction. Because both signing and climbing require use of the hands, all students were top-roped, allowing them to let go of the wall and still be supported.

We placed one interpreter at the top of the twenty-five foot building, so the climber/student could look up; we placed another at the foot of the wall so the climber/student could look down. This triangulation enabled my students to climb, as well as communicate toward their desired direction. Because both signing and climbing require use of the hands, all students were top-roped, allowing them to let go of the wall and still be supported.

.

I like to find metaphors in everything, and this one was significant to me. I wanted my students to know, “You can let go of everything for just this moment in time and still be held up. We won’t let you fall. We won’t let you down. Tell us what you need!”

I like to find metaphors in everything, and this one was significant to me. I wanted my students to know, “You can let go of everything for just this moment in time and still be held up. We won’t let you fall. We won’t let you down. Tell us what you need!”

.

The day was successful in many respects. It marked the beginning of relationships that laid foundations for trust. I was able to take these same students to a YMCA Deaf Camp for five consecutive years following that first rock-climbing experience. I was invited to eat dinner with my students’ families, who were often too poor to feed themselves adequately. I felt honored and cherished to join them, in full Cambodian tradition, on a beautiful mat laid out on the floor of their apartments. Communication barriers persisted, too, but we ate in celebration of our shared belief that we simply must begin somewhere and that sharing food was a way of sharing love.

The day was successful in many respects. It marked the beginning of relationships that laid foundations for trust. I was able to take these same students to a YMCA Deaf Camp for five consecutive years following that first rock-climbing experience. I was invited to eat dinner with my students’ families, who were often too poor to feed themselves adequately. I felt honored and cherished to join them, in full Cambodian tradition, on a beautiful mat laid out on the floor of their apartments. Communication barriers persisted, too, but we ate in celebration of our shared belief that we simply must begin somewhere and that sharing food was a way of sharing love.

.

In my pursuit for a rock-climbing facility for my students I had met my angel: Michael. I had not told him for, at least, two months that I had recognized him instantly as I walked down the aisle of the sporting goods store. I actually had the thought, “Oh, this is the guy for me!” I fell in love with him instinctively. Michael and I married three years after that rock-climbing Saturday afternoon. At our wedding, we included two interpreters (one for the male voice and one for the female voice). The service was on the grounds of the Long Beach Museum of Art, overlooking the ocean. Catalina Island glistened in the distance. We made our vows as the sun slid over the horizon, before our friends, family, and students. Our cake was shaped in the form of a mountain with a bride and a groom (iron, welded by an artist friend) portrayed as rock climbers. The groom (with welded top hat) was belaying his bride (bedecked with a white lace train) to the top of the mountain.

In my pursuit for a rock-climbing facility for my students I had met my angel: Michael. I had not told him for, at least, two months that I had recognized him instantly as I walked down the aisle of the sporting goods store. I actually had the thought, “Oh, this is the guy for me!” I fell in love with him instinctively. Michael and I married three years after that rock-climbing Saturday afternoon. At our wedding, we included two interpreters (one for the male voice and one for the female voice). The service was on the grounds of the Long Beach Museum of Art, overlooking the ocean. Catalina Island glistened in the distance. We made our vows as the sun slid over the horizon, before our friends, family, and students. Our cake was shaped in the form of a mountain with a bride and a groom (iron, welded by an artist friend) portrayed as rock climbers. The groom (with welded top hat) was belaying his bride (bedecked with a white lace train) to the top of the mountain.

.

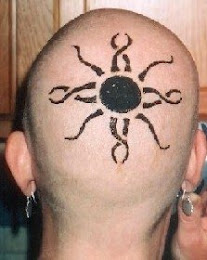

Michael’s best man, during his toast, bestowed on Michael his own title of “Best Man.” There was no man better: a man who was willing to help, to support, to lift up…. “It’s just who he is, because it’s the right thing to be.” And so he is. Michael’s goodness is completely evidenced in his willingness to remain present. Regardless of sacrifices involved, he has never altered his commitment to remaining present. That is my definition of a hero. I have been sure of this since the beginning of our relationship together. We entered the cancer adventure as a unit, each present and ready to accept the challenge of the climb.

Michael’s best man, during his toast, bestowed on Michael his own title of “Best Man.” There was no man better: a man who was willing to help, to support, to lift up…. “It’s just who he is, because it’s the right thing to be.” And so he is. Michael’s goodness is completely evidenced in his willingness to remain present. Regardless of sacrifices involved, he has never altered his commitment to remaining present. That is my definition of a hero. I have been sure of this since the beginning of our relationship together. We entered the cancer adventure as a unit, each present and ready to accept the challenge of the climb.